文章信息

- 吕彬, 刘潇, 谭旺晓, 王小莹, 高秀梅

- LYU Bin, LIU Xiao, TAN Wangxiao, WANG Xiaoying, GAO Xiumei

- 炎性级联反应在心肌梗死发展过程中的作用及药物治疗研究

- Research on the impacts and drug therapy of inflammatory cascade reaction in the development process of myocardial infarction

- 天津中医药大学学报, 2021, 40(4): 424-430

- Journal of Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2021, 40(4): 424-430

- http://dx.doi.org/10.11656/j.issn.1673-9043.2021.04.05

-

文章历史

收稿日期: 2021-04-20

2. 天津中医药大学中药学院, 天津 301617

2. College of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, Tianjin 301617, China

目前,心血管疾病已成为主要的全球性健康问题[1]。据国家心血管病医疗质量管理与控制中心预测,至2030年,中国35~84岁人群中患心肌梗死、心绞痛、冠心病猝死等事件总数将超过50%。急性心肌梗死(AMI)是冠状动脉急性、持续性缺血缺氧所引起的心肌坏死[2],其发病机制是在冠状动脉粥样硬化的基础上,斑块破裂引起血小板聚集形成血栓,造成管腔严重狭窄,减少了对心脏的富氧血液供应,导致心肌组织持续缺血缺氧,最终引起局部心肌细胞凋亡、坏死[3]。AMI具有高发病率和高病死率的特点,据《中国心血管病调查报告2018》调查显示,中国AMI发病率约为55/10万人,近十年发病人数增加2倍以上;2002—2016年中国AMI病死率大幅升高,总体呈快速上升趋势[4]。

AMI后的心力衰竭是引起死亡的主要原因,其主要的病理生理过程是心室重塑(VR),直接影响AMI患者的预后。VR是指AMI后的左心室进行性扩张和形态学改变,包括心室容积、心室壁厚度及结构变化等[5],主要是由梗死后心肌血流动力学参数的改变及心脏收缩舒张障碍引起的[6]。研究表明[7-9],炎性级联反应、氧化应激、细胞自噬等均参与了VR的过程,其中炎性级联反应是引起VR的最重要因素。在梗死的心肌中,坏死的心肌细胞释放危险信号,激活自身免疫反应。炎性途径在调节涉及梗死心脏的损伤、修复和重塑的多种细胞过程中起着至关重要的作用。适当的炎症能够清除凋亡的细胞,减少梗死区面积,促进瘢痕形成并防止梗死范围扩大,有助于缺血心肌的恢复[10];过度的炎症则会加剧心肌损伤,促进心室重塑及心肌纤维化的形成。由于炎症因子可能参与损伤性、修复性和再生性反应,因此它们是治疗心肌梗死的关键。文章对炎性级联反应在AMI发展过程中的作用及临床治疗药物进行综述,为临床治疗AMI炎症提供参考。

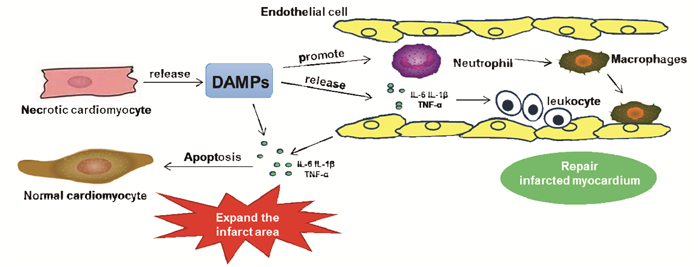

1 炎性级联反应在AMI发展过程中的作用梗死后心肌修复的过程可以分为3个部分重叠的阶段:炎症反应期、增生期和成熟期[11]。AMI发生后,梗死区域凋亡的心肌细胞会产生强烈的炎性级联反应。在炎症反应期,凋亡的心肌细胞释放大量的损伤相关分子(DAMPs),包括高迁移率族蛋白B1(HMGB1)、热休克蛋白(HSPs)、细胞外RNA及白介素-1α(IL-1α)等,激活炎症小体并形成先天免疫反应[12-15],同时会促进凋亡的心肌细胞释放促炎性细胞因子,包括肿瘤坏死因子-α(TNF-α)、白细胞介素-1β(IL-1β)、白介素-6(IL-6)等。之后,补体级联反应被激活,产生活性氧(ROS)并促进大量的中性粒细胞浸润到梗死区域。中性粒细胞浸润后,单核细胞被募集到梗死区域,具有修复特性的单核细胞亚群在成纤维细胞和内皮细胞活化、促进瘢痕形成中起重要作用。促炎性细胞因子表达的上升会诱导浸润的单核细胞转变为巨噬细胞,并顺序协调受损组织的消化;还能够诱导黏附因子和趋化因子的合成,促进白细胞募集到梗死区域。此时,炎症反应开始消退,心肌修复进入成熟阶段,巨噬细胞和募集的白细胞会释放出细胞因子,促进肌成纤维细胞和血管细胞生成,形成稳定的瘢痕[16],梗死区域不再变化。

然而,过度或消除不及时的炎症反应可能会延长缺血性损伤,促进梗死区域外正常心肌细胞的凋亡[17]。在非梗死区域,中性粒细胞的聚集能够引起正常心肌细胞的促凋亡反应,扩大缺血性损伤;促炎性细胞因子的显着上调也可以延伸至非梗死区域,引发蛋白酶、活性氧及细胞因子表达升高,从而促进非梗死心肌的间质纤维化和胶原蛋白沉积,进而导致心室功能障碍[18]。非梗死区域的正常心肌细胞能够响应DAMPs,自身释放大量的促炎性细胞因子,促进白细胞向非梗死区域浸润,并与正常的心肌细胞相互作用,引起心肌细胞的凋亡。此外,多项研究表明,抑制炎症反应,减少梗死区域炎性浸润对促进梗死愈合具有重要意义。在急性心肌梗死再灌注的大型动物模型中,抗中性粒细胞血清治疗组与生理盐水组相比,梗死面积平均减少43%,且梗死区域无明显中性粒细胞浸润[19];在小鼠急性心肌梗死模型建立前1周给予rAAV9-Wnt11,能够减少梗死心肌中的炎性浸润,改善小鼠心脏功能及生存率[20]。因此,以炎症作为靶标治疗AMI也引起了越来越多的关注,已成为临床治疗AMI的新方向。炎症在AMI发展过程中的作用见图 1。

|

| 图 1 炎症在AMI发展过程中的作用 |

在炎症损伤假说出现之前,已提出了采用皮质类固醇激素治疗AMI[21]。糖皮质激素具有较强的抗炎效果,能够抑制NF-κB等促炎性介质的转录[22]。然而,实验结果表明,使用糖皮质激素治疗AMI会降低死细胞清除率,易导致疤痕变薄,不利于梗死愈合,且会出现心室动脉瘤并增加心脏破裂的风险[23-24]。此外,并无临床研究支持采用糖皮质激素类药物治疗有益于AMI患者预后,且会出现高血糖、水肿等其他不良反应。因此,ST抬高型心肌梗死管理指南中不建议采用糖皮质激素类药物进行治疗[25]。

2.2 非甾体类抗炎药非甾体类抗炎药(NSAIDs)是通过抑制环氧合酶(COX)来抑制花生四烯酸中类固醇的产生,进而发挥抗炎作用[26]。NSAIDs曾广泛应用于梗死后炎症的临床治疗,然而调查发现,使用NSAIDs治疗的AMI患者,远期死亡率较未使用NSAIDs治疗的患者高出30%。临床研究表明,NSAIDs的使用与心肌梗死后的不良结局之间存在关联[27]。NSAIDs会导致梗死面积扩大,使心室壁张力作用于可变形心肌的时间延长,从而导致动脉瘤的形成和心脏破裂[28-29]。此外,NSAIDs还会引起血压升高,肾血流量减少,血小板聚集增加以及胃肠道出血等不良反应。因此,目前指南建议患者在治疗过程中停止使用NSAIDs。

2.3 TNF-α受体阻滞剂TNF-α是在心梗早期释放的炎症因子,可促进炎症发展并引起心脏功能障碍[30]。临床研究表明,采用TNF-α受体阻滞剂治疗后,24 h内患者嗜中性粒细胞数和血浆IL-6水平降低,但血小板单核细胞聚集体却明显增加[31]。此外,关于依那西普(Etanercept)和英利昔单抗(Infliximab)的临床实验也显示出患者不良心血管事件呈剂量依赖性增加[32-33]。TNF-α受体分为两种:TNFR1和TNFR2。TNFR1的募集会促进炎症及心肌细胞凋亡,而TNFR2则具有保护心肌细胞存活的作用[34]。非选择性地抑制TNF-α受体,不仅抑制了TNFR1的促炎作用,同时也消除了TNFR2的保护作用,这可能是导致患者预后不良的重要原因。

2.4 C5补体抑制剂补体级联反应在AMI早期被激活,刺激内皮细胞释放促炎性细胞因子,促进白细胞募集,最终引起心肌细胞凋亡[16]。据报道,抑制C5激活可以减少梗死区域中性粒细胞浸润,抑制梗死范围扩大[35]。培珠单抗(Pexelizumab)是一种人源C5单克隆抗体,可以明显降低患者血液中C-反应蛋白和IL-6水平[36],但其在临床实验中未达到预期的治疗效果。COMMA(血管成形术治疗心肌梗死中的补体抑制)试验显示培珠单抗能够降低患者90 d死亡率[37];COMPLY(溶栓治疗心肌梗死中的补体抑制)试验中采用培珠单抗治疗未能减少STEMI患者的梗塞面积或减轻主要不良心血管事件[38],在APEX-AMI(急性心肌梗死中培珠单抗的评估)试验中也未发现培珠单抗对患者30 d病死率及3个月内主要不良心血管事件产生影响[39]。因此,对培珠单抗对AMI的治疗作用仍有待评估。

2.5 IL-1受体拮抗剂阿那白滞素(Anakinra)是一种IL-1受体激动剂,能够竞争性的结合IL-1受体,进而阻断IL-1β与受体结合[40]。阿那白滞素能够改善AMI后的心室重塑及心脏功能,且对梗死愈合及疤痕的产生无明显影响[41]。已完成的两项临床实验VCU-ART(弗吉尼亚联邦大学急性重塑实验)和VCU-ART2均显示阿那白滞素具有良好的耐受性,且能够明显降低患者血液中C-反应蛋白水平,并明显降低了心衰的发病率[42-43]。Morton[44]和Sonnino[45]的研究也证实了阿那白滞素能够明显降低AMI患者C-反应蛋白及IL-6水平。目前,弗吉尼亚联邦大学正在进行第3项临床实验,目的是探究不同剂量阿那白滞素对AMI的治疗作用。

卡那单抗(Canakinumab)是一种人源IL-1β单克隆抗体,仅能特异性靶向结合IL-1β,与IL-1家族其他成员无交叉反应,且与卡那单抗形成复合物的IL-1β无法与IL-1受体结合[46]。CANTOS(卡那单抗抗炎、抗血栓形成结果研究)试验纳入了10 061例患者,中位随访时间为3.7年,发现每3个月皮下注射1次卡那单抗,可以使复发性不良心血管事件发生率下降15%[47]。随后的二级分析发现,首次注射卡那单抗3个月内患者血液中C-反应蛋白明显降低,且不良心血管事件发生率下降25%[48]。此外,动物实验显示利纳西普及双醋瑞因等其他IL-1受体拮抗剂也能够减轻AMI后的炎症反应,改善心脏功能和心室重塑[40, 49]。目前研究表明IL-1受体拮抗剂具有明显的临床疗效,可能会成为未来临床以炎症信号为靶标治疗AMI的首选药物。

2.6 他汀类药物目前,临床治疗AMI的常用药为他汀类药物。他汀类药物主要具有降血脂作用,能够阻碍胆固醇合成,降低血清、肝脏及主动脉中的胆固醇、低密度脂蛋白水平,是目前临床治疗动脉粥样硬化和冠心病的首选药物。他汀类药物本身具有一定的抗炎作用,能够降低患者C-反应蛋白、IL-6、TNF-α的水平[50-52],但作用效果不甚明显,且并不是临床规定抗炎用药。在近期的一项研究中,研究者以非致命性心肌梗死、心源性死亡、中风及动脉血运重建作为主要心血管事件,发现较高的基线CRP水平和LDL水平与主要血管事件发生风险增加有关,使用他汀类药物治疗后,LDL的降低对主要血管事件的功效与基线时的CRP浓度无关,证实他汀类药物主要是通过降低LDL水平发挥改善心功能的作用,与血清中CRP的含量关系不大[53]。因此,对于其是否通过抗炎发挥改善心功能的作用,目前仍存在一些争议。

3 中药对AMI炎症的治疗作用现如今,以炎症信号为靶标治疗AMI的研究仍存在很多问题。现代西药对于AMI后炎症具有一定的治疗作用,但大多数药物具有明显的不良反应,预后较差。近年来,传统中药对心血管疾病的治疗效果逐渐显现,其作用机制也引起了广泛关注。相对于化学药物,中药具有副作用小、安全性高的特点,且由于其种类繁多,在新药开发方面可面临更多的选择。大量的研究结果表明,中药对AMI的治疗作用与抗炎效果有关。据报道[54],麝香酮能够通过抑制NF-κB和NLRP3的活化,减轻了心脏巨噬细胞介导的慢性炎症反应,降低MI小鼠体内促炎性细胞因子的水平,从而改善心脏功能。白术内酯Ⅱ和Ⅲ预处理能够明显减轻MI小鼠心肌组织炎性细胞浸润,抑制血小板活化及心肌纤维化[55]。陈琳琳等[56]发现,姜黄素能够通过促进抑炎因子IL-10上调,抑制iNOS和NF-κB通路的激活发挥抑制梗死后炎症的作用,从而调节MI小鼠心室重塑。芍药苷能够抑制诱导型一氧化氮合酶(iNOS)的活性,并通过抑制IL-6、TNF-α、IL-1β及NF-κB的表达,进而促进梗死面积减小,发挥心脏保护作用[57]。传统中药复方黄芪保心汤能够降低心肌梗死后心力衰竭大鼠IL-6、TNF-α水平及基质金属蛋白酶MMP-2、MMP-9的表达,改善心脏形态结构和心肌重塑[58];芪苈强心胶囊能够通过抑制NF-κB通路及TGF-β1/ Smad3通路,进而抑制AMI模型大鼠的心室重塑[59]。

目前,通过抗炎治疗AMI的中药仍有待研究。尽管临床上已证实中药对于AMI具有一定的防治作用,中成药如芪参益气滴丸、血脂康等[60-61]也已被报道具有减少梗死面积和心肌损伤、改善心功能等作用,但大多数临床研究的质量仍有待提高[62]。其次,中药对AMI炎症的抑制仍处于基础实验阶段,目前尚缺乏临床证据。此外,中药具有多成分、多靶点的特点,其主要是通过各成分与不同通路、靶点间的协同作用而发挥功效的。因此,对其作用机制的阐述也存在着较大的困难。

4 结语炎性级联反应在AMI的发生发展过程中发挥着重要作用,以炎症作为靶标治疗AMI也引起了越来越多的关注。临床上已开发出多种治疗药物,但大多数药物均有一定的不良反应,导致患者不良心血管事件的发生风险增加,且药效得不到保障。临床治疗AMI炎症反应的药物研究进展见开放科学(资源服务)标识码(OSID)。中药安全性较高,预后良好,已被证实对CVD具有较好的防治效果。尽管中药治疗AMI炎症仍存在着较多的问题,但随着中药现代化以及中药药理学理论研究的不断发展,对于中药药效物质基础及作用机制的研究也日渐趋于完善,利用中药治疗AMI炎症,可成为临床研究的新方向。

| [1] |

MENDOZA-HERRERA K, PEDROZA-TOBIAS A, HERNANDEZ-ALCARAZ C, et al. Attributable burden and expenditure of cardiovascular diseases and associated risk factors in mexico and other selected mega-countries[J]. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 2019, 16(20): 4041-4066. DOI:10.3390/ijerph16204041 |

| [2] |

WARNER M J, BHIMJI S S. Myocardial infarction, inferior[A]. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island (FL), 2018.

|

| [3] |

CHHIBBER-GOEL J, SINGHAL V, BHOWMIK D, et al. Linkages between oral commensal bacteria and atherosclerotic plaques in coronary artery disease patients[J]. NPJ Biofilms Microbiomes, 2016, 2: 7-19. DOI:10.1038/s41522-016-0009-7 |

| [4] |

胡盛寿, 高润霖, 刘力生, 等. 《中国心血管病报告2018》概要[J]. 中国循环杂志, 2019, 34(3): 209-220. HU S S, GAO R L, LIU L S, et al. Summary of the 2018 report on cardiovascular diseases in China[J]. Chinese Circulation Journal, 2019, 34(3): 209-220. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1000-3614.2019.03.001 |

| [5] |

刘铭雅, 魏盟. 心肌梗死后心力衰竭发生机制及诊治进展[J]. 内科理论与实践, 2014, 9(1): 21-25. LIU M Y, WEI M. The pathogenesis, diagnosis and treatment progress of heart failure after myocardial infarction[J]. Internal Medicine Theory Practice, 2014, 9(1): 21-25. |

| [6] |

WANG C, HOU J, DU H, et al. Anti-depressive effect of Shuangxinfang on rats with acute myocardial infarction: promoting bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells mobilization and alleviating inflammatory response[J]. Biomedicine Pharmacotherapy, 2019, 111(32): 19-30. |

| [7] |

顾文超, 周晓慧, 林芳, 等. T细胞亚群在心室重构中的作用研究进展[J]. 中国比较医学杂志, 2017, 27(10): 85-88. GU W C, ZHOU X H, LIN F, et al. Advances in research on the role of T cell subsets in ventricular remodeling[J]. Chinese Journal of Comparative Medicine, 2017, 27(10): 85-88. |

| [8] |

SAHEERA S, NAIR R R. Accelerated decline in cardiac stem cell efficiency in Spontaneously hypertensive rat compared to normotensive Wistar rat[J]. PLoS One, 2017, 12(12): e0189129. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0189129 |

| [9] |

SHAO T, ZHANG Y, TANG R, et al. Effects of milrinone on serum IL-6, TNF-α, Cys-C and cardiac functions of patients with chronic heart failure[J]. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 2018, 16(5): 4162-4166. |

| [10] |

刘雪岩, 李成花, 杨萍. 炎症反应在心梗后心衰发病过程中的作用研究进展[J]. 分子影像学杂志, 2017, 40(1): 81-84. LIU X Y, LI C H, YANG P. Progress in effects and regulation of inflammatory response in post-infarction heart failure[J]. Journal of Molecular Imaging, 2017, 40(1): 81-84. DOI:10.3969/j.issn.1674-4500.2017.01.24 |

| [11] |

FRANGOGIANNIS N G. Regulation of the inflammatory response in cardiac repair[J]. Circulation Research, 2012, 110(1): 159-173. DOI:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.111.243162 |

| [12] |

RANEK M J, STACHOWSKI M J, KIRK J A, et al. The role of heat shock proteins and co-chaperones in heart failure[J]. Philosophical Transactions-Royal Society. Biological Sciences, 2018, 373(1738). |

| [13] |

CHEN C, FENG Y, ZOU L, et al. Role of extracellular RNA and TLR3-Trif signaling in myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury[J]. Journal of the AmericanHeartAssociation, 2014, 3(1): e000683. |

| [14] |

LUGRIN J, PARAPANOV R, ROSENBLATT-VELIN N, et al. Cutting edge: IL-1α is a crucial danger signal triggering acute myocardial inflammation during myocardial infarction[J]. Journalof Immunology, 2015, 194(2): 499-503. |

| [15] |

LIN Y, CHEN L, LI W, et al. Role of high-mobility group box-1 in myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury and the effect of ethyl pyruvate[J]. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 2015, 9(4): 1537-1541. DOI:10.3892/etm.2015.2290 |

| [16] |

FRANGOGIANNIS N G. The immune system and the remodeling infarcted heart: cell biological insights and therapeutic opportunities[J]. Journalof Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 2014, 63(3): 185-195. DOI:10.1097/FJC.0000000000000003 |

| [17] |

ENTMAN M L, YOUKER K, SHOJI T, et al. Neutrophil induced oxidative injury of cardiac myocytes. A compartmented system requiring CD11b/CD18-ICAM-1 adherence[J]. Journalof Clinical Investigation, 1992, 90(4): 1335-1345. DOI:10.1172/JCI115999 |

| [18] |

IBARRA-LARA L, SANCHEZ-AGUILAR M, SORIA-CASTRO E, et al. Clofibrate treatment decreases inflammation and reverses myocardial infarction-induced remodelation in a rodent experimental model[J]. Molecules, 2019, 24(2): 270-283. DOI:10.3390/molecules24020270 |

| [19] |

ROMSON J L, HOOK B G, KUNKEL S L, et al. Reduction of the extent of ischemic myocardial injury by neutrophil depletion in the dog[J]. Circulation, 1983, 67(5): 1016-1023. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.67.5.1016 |

| [20] |

MORISHITA Y, KOBAYASHI K, KLYACHKO E, et al. Wnt11 gene therapy with adeno-associated virus 9 improves recovery from myocardial infarction by modulating the inflammatory response[J]. Scientific Reports, 2016, 6: 21705. DOI:10.1038/srep21705 |

| [21] |

LIBBY P, MAROKO P R, BLOOR C M, et al. Reduction of experimental myocardial infarct size by corticosteroid administration[J]. Journalof Clinical Investigation, 1973, 52(3): 599-607. DOI:10.1172/JCI107221 |

| [22] |

RHEN T, CIDLOWSKI J A. Antiinflammatory action of glucocorticoids-new mechanisms for old drugs[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2005, 353(16): 1711-1723. DOI:10.1056/NEJMra050541 |

| [23] |

HAMMERMAN H, KLONER RA, HALE S, et al. Dose-dependent effects of short-term methylprednisolone on myocardial infarct extent, scar formation, and ventricular function[J]. Circulation, 1983, 68(2): 446-452. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.68.2.446 |

| [24] |

KLONER R A, FISHBEIN M C, LEW H, et al. Mummification of the infarcted myocardium by high dose corticosteroids[J]. Circulation, 1978, 57(1): 56-63. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.57.1.56 |

| [25] |

O'GARA P T, KUSHINER F G, ASCHEIM D D, et al. 2013 ACCF/AHA guideline for the management of ST-elevation myocardial infarction: executive summary: a report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Task Force on Practice Guidelines: developed in collaboration with the American College of Emergency Physicians and Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions[J]. Catheterizationand Cardiovascular Interventions, 2013, 82(1): E1-27. |

| [26] |

ANTMAN E M, DEMETS D, LOSCALZO J. Cyclooxygenase inhibition and cardiovascular risk[J]. Circulation, 2005, 112(5): 759-770. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.105.568451 |

| [27] |

SILVERMAN H S, PFEIFER M P. Relation between use of anti-inflammatory agents and left ventricular free wall rupture during acute myocardial infarction[J]. American Journal of Cardiology, 1987, 59(4): 363-364. DOI:10.1016/0002-9149(87)90817-4 |

| [28] |

PFEFFER M A, BRAUNWALD E. Ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction: Experimental observations and clinical implications[J]. Circulation, 1990, 81(4): 1161-1172. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.81.4.1161 |

| [29] |

JUGDUTT B I, BASUALDO C A. Myocardial infarct expansion during indomethacin or ibuprofen therapy for symptomatic post infarction pericarditis. Influence of other pharmacologic agents during early remodelling[J]. Canadian Journal of Cardiology, 1989, 5(4): 211-221. |

| [30] |

YOKOYAMA T, VACA L, ROSSEN R D, et al. Cellular basis for the negative inotropic effects of tumor necrosis factor-alpha in the adult mammalian heart[J]. Journalof Clinical Investigation, 1993, 92(5): 2303-2312. DOI:10.1172/JCI116834 |

| [31] |

PADFIELD G J, DIN J N, KOUSHIAPPI E, et al. Cardiovascular effects of tumour necrosis factor α antagonism in patients with acute myocardial infarction: a first in human study[J]. Heart, 2013, 99(18): 1330-1335. DOI:10.1136/heartjnl-2013-303648 |

| [32] |

MANN D L, MCMURRAY J J, PACKER M, et al. Targeted anticytokine therapy in patients with chronic heart failure: results of the Randomized Etanercept Worldwide Evaluation (RENEWAL)[J]. Circulation, 2004, 109(13): 1594-1602. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000124490.27666.B2 |

| [33] |

COLETTA A P, CLARK A L, BANARJEE P, et al. Clinical trials update: RENEWAL (RENAISSANCE and RECOVER) and ATTACH[J]. European Journal of Heart Failure, 2002, 4(4): 559-561. DOI:10.1016/S1388-9842(02)00121-6 |

| [34] |

MEDLER J, WAJANT H. Tumor necrosis factor receptor-2(TNFR2): an overview of an emerging drug target[J]. Expert Opinion on Therapeutic Targets, 2019, 23(4): 295-307. DOI:10.1080/14728222.2019.1586886 |

| [35] |

PISCHKE S E, GUSTAVSEN A, ORREM H L, et al. Complement factor 5 blockade reduces porcine myocardial infarction size and improves immediate cardiac function[J]. Basic Research Cardiology, 2017, 112(3): 20. DOI:10.1007/s00395-017-0610-9 |

| [36] |

THEROUX P, ARMSTRONG P W, MAHAFFEY K W, et al. Prognostic significance of blood markers of inflammation in patients with ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction undergoing primary angioplasty and effects of pexelizumab, a C5 inhibitor: a substudy of the Comma trial[J]. Eurpean Heart Journal, 2005, 26(19): 1964-1970. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehi292 |

| [37] |

GRANGER CB, MAHAFFEY KW, WEAVER WD, et al. Pexelizumab, an anti-C5 complement antibody, as adjunctive therapy to primary percutaneous coronary intervention in acute myocardial infarction: the Complement inhibition in myocardial infarction treated with angioplasty (COMMA) trial[J]. Circulation, 2003, 108(10): 1184-1190. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000087447.12918.85 |

| [38] |

MAHAFFEY KW, GRANGER CB, NICOLAU JC, et al. Effect of pexelizumab, an anti-C5 complement antibody, as adjunctive therapy to fibrinolysis in acute myocardial infarction: the Complement inhibition in myocardial infarction treated with thrombolytics (COMPLY) trial[J]. Circulation, 2003, 108(10): 1176-1183. DOI:10.1161/01.CIR.0000087404.53661.F8 |

| [39] |

APEX AMI INVESTIGATORS, ARMSTRONG P W, GRAN-GER C B, et al. Pexelizumab for acute ST-elevation myocardial infarction in patients undergoing primary percutaneous coronary intervention: a randomized controlled trial[J]. JAMA, 2007, 297(1): 43-51. DOI:10.1001/jama.297.1.43 |

| [40] |

VAN TASSELL B W, VARMA A, SALLOUM F N, et al. Interleukin-1 trap attenuates cardiac remodeling after experimental acute myocardial infarction in mice[J]. Journal Cardiovascular Pharmacology, 2010, 55(2): 117-122. DOI:10.1097/FJC.0b013e3181c87e53 |

| [41] |

VAN TASSELL B W, TOLDO S, MEZZAROMA E, et al. Targeting interleukin-1 in heart disease[J]. Circulation, 2013, 128(17): 1910-1923. DOI:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.113.003199 |

| [42] |

ABBATE A, VAN TAWWELL B W, BIONDI-ZOCCAI G, et al. Effects of interleukin-1 blockade with anakinra on adverse cardiac remodeling and heart failure after acute myocardial infarction from the virginia commonwealth university-anakinra remodeling trial (2) (VCU-ART2) pilot study][J]. American Journal of Cardiology, 2013, 111(10): 1394-1400. DOI:10.1016/j.amjcard.2013.01.287 |

| [43] |

ABBATE A, KONTOS M C, GRIZZARD J D, et al. Interleukin-1 blockade with anakinra to prevent adverse cardiac remodeling after acute myocardial infarction (virginia commonwealth university anakinra remodeling trial[VCU-ART] pilot study)[J]. American Journal of Cardiology, 2010, 105(10): 1371-1377.e1. DOI:10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.12.059 |

| [44] |

MORTON A C, ROTHMAN A M, GREENWOOD J P, et al. The effect of interleukin-1 receptor antagonist therapy on markers of inflammation in non-ST elevation acute coronary syndromes: the Mrc-ila Heart Study[J]. European Heart Journal, 2015, 36(6): 377-384. DOI:10.1093/eurheartj/ehu272 |

| [45] |

SONNINO C, CHRISTOPHER S, ODDI C, et al. Leukocyte activity in patients with ST-segment elevation acute myocardial infarction treated with anakinra[J]. Molecular Medicine, 2014, 2(7): 486-489. |

| [46] |

RONDEAU J M, RAMAGE P, ZURINI M, et al. The molecular mode of action and species specificity of canakinumab, a human monoclonal antibody neutralizing IL-1β[J]. MAbs, 2015, 7(6): 1151-1160. DOI:10.1080/19420862.2015.1081323 |

| [47] |

RIDKER P M, EVERETT B M, THUREN T, et al. Antii-nflammatory therapy with canakinumab for atherosclerotic disease[J]. The New England Journal of Medicine, 2017, 377(12): 1119-1131. DOI:10.1056/NEJMoa1707914 |

| [48] |

RIDKER P M, MACFADYEN J G, EVERETT B M, et al. Relationship of C-reactive protein reduction to cardiovascular event reduction following treatment with canakinumab: a secondary analysis from the cantos randomised controlled trial[J]. Lancet, 2018, 391(10118): 319-328. DOI:10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32814-3 |

| [49] |

TORINA A G, REICHERT K, LIMA F, et al. Diacerein improves left ventricular remodeling and cardiac function by reducing the inflammatory response after myocardial infarction[J]. PLoS One, 2015, 10(3): e0121842. DOI:10.1371/journal.pone.0121842 |

| [50] |

REN Y, ZHU H, FAN Z, et al. Comparison of the effect of rosuvastatin versus rosuvastatin/ezetimibe on markers of inflammation in patients with acute myocardial infarction[J]. Experimental and Therapeutic Medicine, 2017, 14(5): 4942-4950. |

| [51] |

SPOSITO A C, SANTOS S N, DE FRAIA E C, et al. Timing and dose of statin therapy define its impact on inflammatory and endothelial responses during myocardial infarction[J]. Arteriosclerosis Thrombosis Vascular Biology, 2011, 31(5): 1240-1246. DOI:10.1161/ATVBAHA.110.218685 |

| [52] |

GAVAZZONI M, GORGA E, DEROSA G, et al. High-dose atorvastatin versus moderate dose on early vascular protection after ST-elevation myocardial infarction[J]. Drug Design Development and Therapy, 2017, 11(2): 3425-3434. |

| [53] |

STOREY B C, STAPLIN N, HAYNES R, et al. Lowering LDL cholesterol reduces cardiovascular risk independently of presence of inflammation[J]. Kidney International, 2018, 93(4): 1000-1007. DOI:10.1016/j.kint.2017.09.011 |

| [54] |

DU Y, GU X, MENG H, et al. Muscone improves cardiac function in mice after myocardial infarction by alleviating cardiac macrophage-mediated chronic inflammation through inhibition of NF-κB and NLRP3 inflammasome[J]. American Journal of Translational Research, 2018, 10(12): 4235-4246. |

| [55] |

杨文龙. 白术内酯Ⅱ和Ⅲ预处理对小鼠心梗后心脏保护作用研究[D]. 上海: 上海交通大学, 2017. YANG W L. Protective effect of a tractylodes II and III on the heartafter myocardial infarction in a mice model[D]. Shanghai: Shanghai Jiaotong University, 2017. |

| [56] |

陈琳琳. 姜黄素对小鼠心肌梗死后心室重构的保护作用及机制研究[D]. 广州: 南方医科大学, 2014. CHEN L L. Studies on the protective effects and mechanism of curcumin in ventricular remodeling after myocardial infarction in mice[D]. Guangzhou: Southern Medical University, 2014. |

| [57] |

CHEN C, DU P, WANG J. Paeoniflorin ameliorates acute myocardial infarction of rats by inhibiting inflammation and inducible nitric oxide synthase signaling pathways[J]. Molecular Medicine Reports, 2015, 12(3): 3937-3943. DOI:10.3892/mmr.2015.3870 |

| [58] |

张庆, 刘敏, 梁田, 等. 黄芪保心汤对心肌梗死后心衰大鼠心室重构及相关炎性因子影响的研究[J]. 新中医, 2019, 51(3): 8-12. ZHANG Q, LIU M, LIANG T, et al. Study on the effect of Huangqi Baoxin Tang on ventricular remodeling and related inflammatory factors in rats with heart failure after myocardial infarction[J]. Journal of New Chinese Medicine, 2019, 51(3): 8-12. |

| [59] |

HAN A, LU Y, ZHENG Q, et al. Qiliqiangxin attenuates cardiac remodeling via inhibition of TGF-β1/Smad3 and NF-κB signaling pathways in a rat model of myocardial infarction[J]. Cellular Physiology And Biochemistry, 2018, 45(5): 1797-1806. DOI:10.1159/000487871 |

| [60] |

陆宗良. 血脂康调整血脂对冠心病二级预防的研究[C]. 中华医学会老年医学分会. 第七届全国老年医学学术会议暨海内外华人老年医学学术会议论文汇编. 中华医学会老年医学分会: 中华医学会, 2004. LU Z L. Secondary prevention effect of Xuezhikangon coronary heart disease[C]. Geriatrics branch of Chinese Medical Association. The 7th National geriatrics academic conference and overseas Chinese geriatrics academic conference. Geriatrics branch of Chinese Medical Association: Chinese Medical Association, 2004. |

| [61] |

商洪才. 芪参益气滴丸对心肌梗死二级预防的临床试验研究通过专家组验收[J]. 天津中医药, 2010, 27(4): 266. SHANG H C. The clinical trial of Qishen Yiqi Dropping Pill on secondary prevention of myocardial infarction was accepted by the expert group[J]. Tianjin University of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 2010, 27(4): 266-266. |

| [62] |

WANG Y, XIAO L, MU W, et al. A summary and evaluation of current evidence for myocardial infarction with Chinese medicine[J]. Chinese Journal of Integrative Medicine, 2017, 23(12): 948-955. DOI:10.1007/s11655-017-2824-y |

2021, Vol. 40

2021, Vol. 40